Euro Foie Gras awards the Golden Palm to MEP Jérémy Decerle

MEPs, members of the permanent and regional representations to the EU, and other friends of foie gras gathered on 11 May at the Representation of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine Region in Brussels to celebrate this delicacy and the women and men who produce it. It was also an opportunity to thank MEP Jérémy Decerle for his commitment to foie gras production by awarding him the Federation’s Golden Palm.

Christophe Barrailh, President of the Federation, opened the Cocktail of the Circle of Foie Gras Friends by thanking MEPs for their support during the vote on Jérémy Decerle’s implementation report on on-farm animal welfare. “Extensive, family-based, mainly open air and respectful of animal welfare” are the foie gras production specificities that were recognised in this report on 15 February 2022.

The President of Euro Foie Gras then spoke about the avian influenza outbreak that is severely affecting a large number of European countries and the entire poultry sector. “The economic and social consequences for farmers and for our animals are terrible. Euro Foie Gras is convinced that in addition to biosecurity and surveillance measures, which are and will remain the pillars of the fight against avian flu, vaccination is now an essential complementary tool for an efficient fight against this disease,” he stressed.

The Federation also expressed its gratitude to MEP Jérémy Decerle, who has succeeded in highlighting the efforts made by breeders on their farms, while promoting the foie gras production sector. Christophe Barrailh praised “a man of conviction and action, who very quickly became a key MEP in the Agriculture Committee“. In recognition of his work, which played an essential role in the European Parliament’s positive vote in February 2022, the Federation awarded him the Golden Palm and also inducted him as a member of the Circle of Foie Gras Friends.

Jérémy Decerle thanked the Federation and reacted: “I am firmly convinced that farmers have a decisive role to play in Europe and must be defended.” He praised the fat palmipeds rearing method, essentially based on family farms, which offers a significant added value. Euro Foie Gras was also pleased to induct six new MEPs from different countries (Czech Republic, Denmark, Sweden, Poland and France) and also thanked the MEPs already members of the Circle.

The Foie Gras Friends had not been able to meet for more than two years due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The evening was rich in exchanges on the challenges and opportunities of the sector, while tasting delicious appetizers based on fat palmipeds.

How is your European foie gras produced? Second stage: duck rearing in the open air

To learn more about foie gras, we have launched a series on its production in Europe, from the arrival of the ducklings in the farms to the final product. This series will only consider duck foie gras, which makes up the majority of foie gras produced in Europe. However, it is important to note the existence of goose foie gras, which accounts for 7% of the total foie gras production in Europe. Goose foie gras is mainly produced in Hungary, where it has been awarded the “Hungaricum” distinction. In this article, we address the second stage of the production process: the outdoor rearing of ducks.

In November, we described the first stage of rearing ducklings, which first grow up in a heated building so that they can feather themselves enough to go out in the open air.

Later on, the animal is strong enough to access the outdoor course. The open air is a fundamental characteristic of foie gras farming. In total, the animals spend 90% of their lives outdoors. The ducks can move freely among their peers in a natural and healthy environment. They eat 75% cereal feed in the form of pellets or meal.

Valérie van Wynsberghe, owner of the Ferme de la Sauvenière, a Belgian family and artisanal farm, explained to CanalZ* that the duck welfare is a priority for the breeders: “If we want to have quality products, the animal must be raised in good conditions, in a pleasant and healthy environment. This is what we do as much as possible. We have planted fruit trees so that they have shade in the summer, the meadows are reseeded every spring so that they are on grassy paths and not in the mud…“.

In order to prepare the animals for the next phase, assisted feeding, a transition period is used to accustom the animal to feeding by meals, thus developing its fattening capacity. The duck, now about 10 weeks old (depending on the species), will be moved to an indoor collective housing for the fattening phase. This third part of our series will be developed later this year.

*https://canalz.levif.be/news/le-journal-09-10-20/video-normal-1343051.html?cookie_check=1649836066 (from 6’30)

Picture: © CIFOG

Non-EU product imports must meet EU standards

On 16 February 2022, the European Commission opened a public consultation on the application of EU health and environmental standards to imports of agricultural and food products. Here is Euro Foie Gras’ opinion on the matter:

The European Union (EU) is the world’s largest producer of foie gras, accounting for 90% of global production. A definition of raw products (foie gras, magret) is included in the regulation 543/20081 on marketing standards for poultrymeat, which should even be supplemented by a standard on processed products to protect consumers from fraudulent practices. However, competition from other countries such as China, where standards are not as high as in the EU, may increase in the coming decades.

Thus, we believe it is essential to ensure that imports of products from third countries comply with European standards. Otherwise, it would undermine the competitiveness of the European farming sector, which would then face unfair competition from non-EU countries. We therefore call for the same conditions to be imposed on imports.

Foie gras is a gastronomic traditional product. Its production is closely linked to the gastronomic national identity of the five European producing countries – Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain, Hungary and France – and contributes to the European culinary influence around the world.

European foie gras production complies with all regulatory requirements in terms of animal health and welfare, including the European directive 98/58/EC on the protection of animals kept for farming purposes, and even goes beyond these regulatory requirements. Indeed, in 2011, the five European foie gras producing countries proactively adopted the European Charter on breeding of waterfowl for foie gras. This Charter sets out the sector’s commitments based on the 12 principles of the European Commission’s “Welfare Quality Project”. The sector is also developing common animal welfare indicators.

Outdoor breeding and collective housing: the best practices of the European foie gras sector

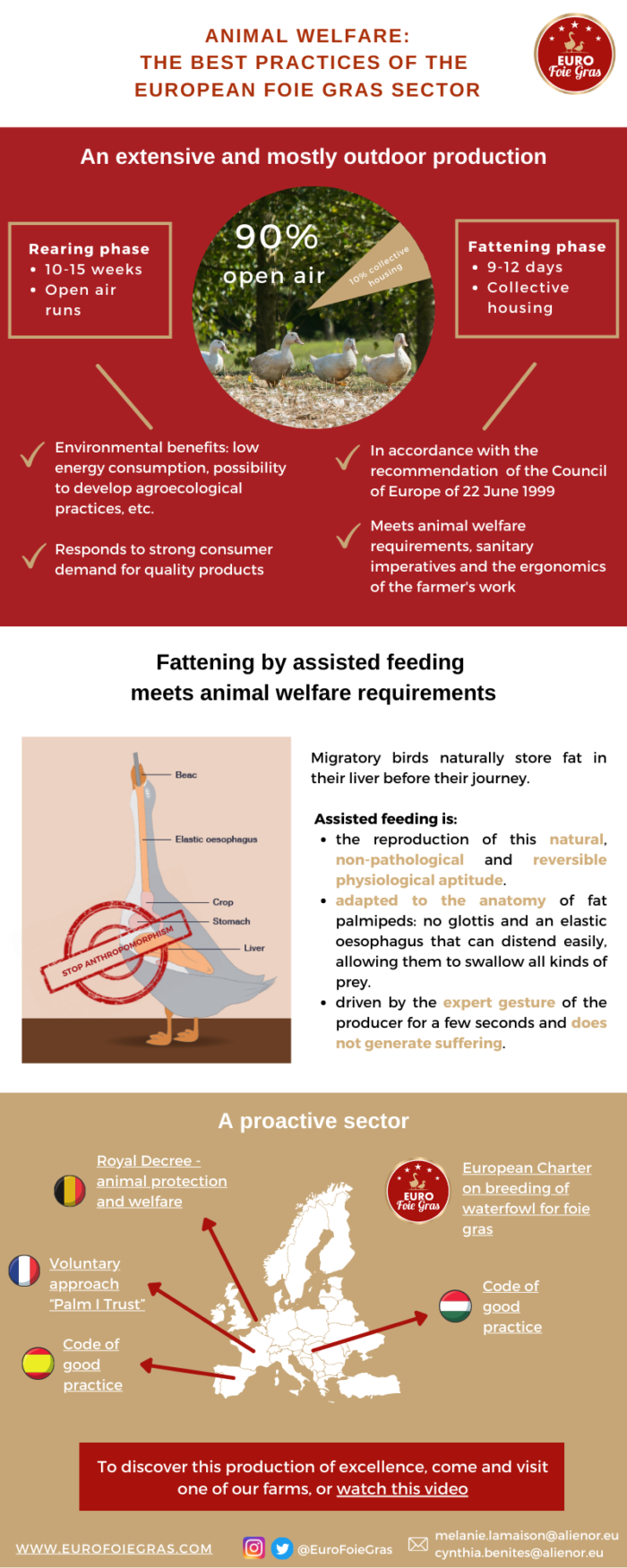

The rearing of fat palmipeds (ducks and geese) is extensive, very often family-run, and mostly in open air. With 90% of the animal’s life spent outdoors, the palmipeds live in collective housing only during the fattening phase and for a limited period between 9 and 15 days depending on the species.

In the five European producing countries – Belgium, Bulgaria, Spain, Hungary and France – fat palmipeds farmers are subject to strict regulatory requirements and controls in terms of animal health and welfare, including the European Directive 98/58/EC on the protection of animals kept for farming purposes.

Euro Foie Gras has always worked and will continue to work so that fat palmipeds are reared in optimal conditions by fully ensuring their well-being while meeting requirements related to sanitary aspects and offering satisfactory working conditions to breeders.

Learn more about European foie gras production by reading our position paper or watching this video.

Joint press release – The European Parliament votes in support of foie gras production

Euro Foie Gras and Copa-Cogeca welcome the positive vote of the European Parliament on Jérémy Decerle’s ‘Implementation report on on-farm animal welfare.’ Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) acknowledged that, “Foie gras production is based on farming procedures that respect animal welfare criteria” and rejected the call to ban assisted feeding of ducks and geese.

Last night, a majority of MEPs voted against two amendments calling for the ban of assisted feeding for foie gras production. The adopted text states that, “The fattening phase, which lasts between 10 and 12 days on average with two meals per day, respects the animal’s biological parameters”. Moreover, it recognises that foie gras production is extensive, open air and mostly takes place on family farms. Fat palmipeds spend 90% of their lives in open air runs, where they can grow freely, surrounded by their peers. This report will feed into the Commission’s revision process of the EU animal welfare legislation.

Christophe Barrailh, President of Euro Foie Gras, reacted, “We very much welcome the support expressed by the Parliament to our sector. Our constant efforts to maintain our specificities and high animal welfare standards have been heard.”

Foie gras production indeed meets all EU animal welfare standards and even goes beyond by following the sector’s own charter adopted in 2013 and by developing animal welfare indicators.

It is also essential to note that, according to the current state of knowledge and available techniques, and unlike claims made for certain products, it is not possible to produce foie gras without assisted feeding.

Euro Foie Gras and Copa-Cogeca have always worked towards and will continue to ensure that fat palmipeds are reared in optimal conditions by fully ensuring their well-being while meeting requirements related to sanitary aspects and offering satisfactory working conditions to breeders.

Co-signed by: Euro Foie Gras (European Federation of foie gras) and Copa-Cogeca (European Farmers and Agri-Cooperatives).

Videos, recipes, tips… Famous chefs tell you all about foie gras!

We wrote about it in October, famous Chefs from four European foie gras producing countries travelled to meet farmers to learn more about this European gastronomic dish. Here are some news from their road trips, rich in emotions and discoveries:

French chefs Pierre Chomet and Matthias Marc, former Top Chef 2021 contestants, met Florian Boucherie, a foie gras producer in Dordogne. At the farm“Guarrigue Haute”, everything is done on site, from breeding to processing.

After a culinary challenge on the theme of foie gras, the two Chefs ended their road trip in the pretty shop of David Pélégris, artisan canner in the centre of Sarlat. Discover their visit in video.

In Belgium, a Chef duo, the Walloon Julien Lapraille and the Flemish Tom Vermeiren, visited the traditional farm of Louis Legrand near Tournai. During the tour, the farmer explained that the fattening of ducks is the reproduction of a natural phenomenon. Indeed, the palmiped is a migratory bird, which can swallow large quantities of food thanks to its lack of glottis and its non cartilaginous oesophagus. This food is then stored as energy in the liver.

Further South, Chefs Ketty Fresneda and Leandro Gil visited a Spanish farm. After observing the ducklings housed indoors to protect them from the cold, they discovered the beautiful outdoor area, where ducks grow freely, with the greatest respect for animal welfare.

In Eastern Europe, and more precisely in Hungary, Wossala Rozina, Chef and owner of her own restaurant, met a goose breeder. Hungary is the largest producer of goose foie gras in the world, with 1132 tons produced in 2020. The Chef then shares a delicious recipe in video, to be tried asap!

You can also find tasty recipes made by the Chefs, as well as lots of information about foie gras on www.ontheroadtofoiegras.com.

This campaign is financed with the help of the European Union through its promotion programme “Sharing Europe’s Gastronomic Heritage”.

The French gastronomic world signs a manifesto in defence of foie gras

Several ecologist mayors of major French cities (Lyon, Strasbourg, Grenoble, Besançon…) have decided to withdraw foie gras from their official events, buffets and receptions. Some of these decisions had already been taken previously, but were recently brought to light by the animalist association PETA.

In order to denounce this boycott and show the support of the gastronomic world, our French member CIFOG (Comité interprofessionnel des palmipèdes à foie gras) has published a manifesto “in support of the French foie gras sector”, signed by, among others, Euro-Toques, l’Académie culinaire de France, l’Association des Toques françaises, les Meilleurs ouvriers de France, le Groupement National des Indépendants, and l’Association française des maîtres restaurateurs. Through this manifesto, the 16 signatory associations undertake to:

“-put foie gras, an inexhaustible source of culinary inspiration, in the spotlight during the festive season and throughout the year;

– write to the concerned mayors to suggest that they reconsider their decision;

– observe the quality of foie gras production methods in France by allowing one or more of their members to visit a farm, an assisted feeding or processing workshop;

– and support the French foie gras sector.”

In addition, many French policy makers have also criticised these decisions. In the Périgord region, for example, 56 elected officials signed a manifesto, stressing that “the political opportunism of a few should not endanger an entire sector of excellence, especially at such a decisive period”.

Foie gras is an exceptional dish, a symbol of French gastronomy. France is the world’s leading producer and consumer of foie gras. In total, the sector represents more than 100,000 direct and indirect jobs, contributing to life in rural areas.

Moreover, it is a highly popular dish. According to the latest CSA study (November 2021), 91% of French people say they eat foie gras. Three out of four French people have already decided to eat foie gras during the end-of-year celebrations.

Euro Foie Gras welcomes initiatives in favour of foie gras and thanks all those who contribute to the defence of this ancestral know-how.

How is your European foie gras produced? First stage: reception and rearing of ducklings

To learn more about foie gras, we are launching a series on its production in Europe, from the arrival of the ducklings in the farms to the final product. This series will only consider duck foie gras, which makes up the majority of foie gras produced in Europe. However, it is important to note the existence of goose foie gras, which accounts for 7% of the total foie gras production in Europe. Goose foie gras is mainly produced in Hungary, where it has been awarded the “Hungaricum” distinction. In this article, we discuss the first stage of the production process: the reception and rearing of the ducklings.

The foie gras production requires a long and meticulous work before it reaches our plates. This work is carried out by passionate breeders, who pass on this tradition from generation to generation. Raising ducks for foie gras production is a process that lasts between 10 and 15 weeks depending on the species. The animals are raised most of the times in artisanal family farms, with the greatest respect for animal welfare.

After the ducklings are born in hatcheries, they arrive at the farm when they are one day old. They are housed in a building heated to 30 degrees to encourage their development and give them time to feather before going outside. The breeders monitor the animals on a daily basis from the very first days.

During this phase, 75% of their diet is cereal, in the form of crumbs and then pellets. Water is available whenever they want, with devices that adapt to the size of the animals according to their growth (mini drinks, then pipets, etc.).

The animals can move around among the other ducklings as they please. Depending on the weather conditions, and when the ducklings are sufficiently feathered, they have access to an outdoor run.

In the second part of this series, we will discuss the rearing phase of ducks in the open air.

First Euro Foie Gras face-to-face meeting in a year and a half

Euro Foie Gras’ Board was delighted to meet on 28 October for their first physical meeting in Brussels since the beginning of the pandemic. The Spanish, Hungarian, Belgian and French members sat around the table to discuss several important issues for the sector.

First of all, the Board gave an economic overview of the foie gras sector. Sales are gradually recovering thanks to the reopening of restaurants, the relaunch of events and the resumption of exports. However, the sector has noted a significant increase in production costs.

On another note, Euro Foie Gras representatives welcomed the launch of the European promotion programme and its website “On the road to foie gras”. Famous chefs, such as Leandro Gil and Ketty Fresdena in Spain, or Rozina Wossala in Hungary, ambassadors of local gastronomy, are travelling through their countries to meet foie gras producers. One goal: spread knowledge among Europeans of this delicious dish and its production process.

The issue of marketing standards was again on the table of the Board, as these are expected to be revised in the course of next year with the publication of the legislative proposal by the European Commission. Euro Foie Gras responded to the European Commission’s public consultation this summer by reiterating its position: to keep the definition of raw foie gras and add a definition for processed foie gras. This is the only way to ensure the quality of foie gras and to effectively protect the consumer.

Lastly, the Federation continued its joint reflection on animal welfare in the context of the implementation of the European “Farm to Fork” Strategy. Providing quality living conditions to their animals at all stages of the rearing process is a daily concern for all fat palmipeds farmers. Therefore, Euro Foie Gras will continue to be a force of proposal on animal welfare by contributing to the discussions on the revision of the European legislation.

Joint Statement – On the European Parliament plenary vote on the Farm to Fork Strategy

Yesterday, the European Parliament voted on its Farm to Fork own initiative report. Food chain actors acknowledge the signal sent by this vote but regret the climate in which the vote took place. We talked about everything but the actual means and solutions when it comes to addressing the multiple blind spots this strategy has created.

Food chain actors all agree with the main goals set out in the Farm to Fork Strategy, we know that changes are necessary, and we remain committed to playing our part in the path towards a transition to a more sustainable food system. Indeed we are already all working in that direction. What we are currently lacking however is new tools and a clearer roadmap. The 2030 deadline is looming, and changes cannot be assimilated overnight.

We are now waiting for concrete proposals from the Commission, especially on the blind spots identified in the ongoing debate such as on the effects of carbon leakage, European strategic autonomy, or consumer prices. With this in mind we also welcome the clear signal sent by the Parliament calling on the European Commission to prepare a comprehensive impact assessment evaluating the impact of its strategy. The data overview presented by the Commission earlier this week[1] would be a great starting point for such a study.

Agriculture and Progress – European Platform for Sustainable Agricultural Production

Agri-Food Chain Coalition – European agri-food chain joint initiative

AnimalHealthEurope – European Animal Medicines Industry

AVEC – European Association of Poultry Processors and Poultry Trade

CEFS – European Association of Sugar Manufacturers

CEJA – European Council of Young Farmers

CEMA – European Agricultural Machinery Industry

CEPM – European Confederation of Maize Production

CEVI – European Confederation of Independent Winegrowers

CIBE – International Confederation of European Beet Growers

Clitravi – Liaison Centre for the Meat Processing Industry in the European Union

COCERAL – European association of trade in cereals, oilseeds, pulses, olive oil, oils and fats, animal feed and agrosupply

Copa-Cogeca – European Farmers and Agri-Cooperatives

CropLife Europe – Europe’s Crop Protection Industry

EBB – European Biodiesel Board

EDA – European Dairy Association

EFFAB – European Forum of Farm Animal Breeders

ELO – European Landowners’ Organization

European Livestock Voice – European Platform of the Livestock Food Chain (with the support of Carni Sostenibili)

Euro Foie Gras – European Federation of Foie Gras

Euroseeds – European Seed Sector

ePURE – European Renewable Ethanol Industry

Fediol – European Vegetable Oil and Protein-Meal Industry Association

FEFAC – European Feed Manufacturers’ Federation

Fertilizers Europe – European Fertilizer Producers

IBC – International Butchers’ Confederation

UECBV – European Livestock and Meat Trades Union